|

| Image of Camp Sackett taken from a daguerrotype and published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, October 4, 1856. |

As conditions deteriorated within the newly established

Kansas Territory, the need for a neutral military force became apparent to keep

the peace (Table 1). The first Territorial

legislature, also called the “Bogus Legislature” had established a pro-slavery

government within Kansas Territory and was upheld by President Pierce. In

February of 1856, Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cook received instructions from

the Secretary of War that troops were to be used within the Territory. On March 26, Colonel Edwin V. Sumner enlisted

the government troops in the growing conflict between free-state and

pro-slavery forces (Robinson 1892).

|

| Table 1: Timeline for troops at Camp Sackett within Kansas Territory events in 1856. |

Troops in Kansas Territory were stationed near military roads at Westport,

Franklin, Baldwin City, Lecompton (Lowe 1906:226) and other strategic

communities and planned as headquarters from which troops could move quickly

when necessary, with food and supplies arriving every ten days (Lowe 1906). In

the spring of 1856, the territorial capital was moved to Lecompton from Shawnee

Mission. This area was then chosen for a primary camp for the government troops

with easy access to the capital. Access to the camp would primarily have been

the Lecompton to Big Springs Road or the California Road (Stuck 1857, Connelly

n.d.).

|

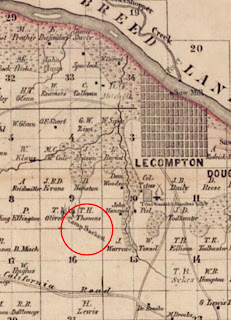

| 1857 Douglas County map by J. Cooper Stuck which shows the location of Camp Sackett in relation to Lecompton and roadways. |

First deployment to the camp was a group of troops under Lt.

James McIntosh around April 23rd, followed by two squadrons under

Col. Sumner (Ewy 1966: 389). The camp

was named for Lt. Col. Delos B. Sackett, the commanding officer early in its

establishment. This camp seems to be

commonly called “Camp Sackett” primarily by those stationed at the camp. Within

the newspaper reports, the camp was known as “the treason camp, near

Lecompton”, “the camp near Lecompton”, or “the U.S. military camp near

Lecompton”. Charles Robinson in his book, The

Kansas Conflict calls it the “Treason Camp” (Robinson 1892). Any designations, however, referring just to

the “camp near Lecompton” should be analyzed and not be confused with the

Titus’ pro-slavery camp near Lecompton.

Titus’ camp is primarily designated as “the pro-slavery camp” but on

occasion is also only called the “camp near Lecompton”.

United States military troops again deployed to the Lecompton

area around May 23rd when Governor Wilson Shannon requested one

company of the 1st Cavalry was to be posted near Lecompton and

another company near Topeka (Mullis 2004). Later, in early June, Lt. Col. Philip

St. George Cooke would arrive from Fort Riley with a compliment of 2nd

Dragoons consisting of 134 men, 124 horses, and one artillery piece (Coakley

2011: 157).

Beginning on and around May 20 (Brown 1880), political

prisoners charged with high treason were delivered to the military camp:

Charles Robinson, George W. Brown, George W. Smith, George W. Deitzler, John

Brown, Jr., and Henry H. Williams. The

charge of treason was imposed on these individuals for supporting a free-state

government and enforced because the pro-slavery government established in 1855 along

with the Topeka Constitution had been federally recognized. Sara Robinson, in

her book Kansas: Interior and Exterior Life gives Camp Sackett the nickname

“Uncle Sam’s Bastille on the Prairie” because of the imprisonment of her

husband and the other men accused of treason.

|

| Left to Right: George W. Brown, John Brown, Jr., George W. Smith, Charles Robinson, Gaius Jenkins, Henry H. Williams, George W. Dietzler. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, October 4, 1856. |

Five political prisoners held on “Traitor Avenue” at Camp

Sackett are as follows:

George W. Smith.

A Pennsylvania native.

Occupation - Judge. Elected by the free-state legislature to serve as

the second territorial governor.

George W. Brown.

A New York native. Occupation - Editor of the Kansas Herald

of Freedom published in Lawrence. He and

Gaius Jenkins were arrested at Westport, MO.

Brown reached the Lecompton camp on May 20 (Brown 1880).

Gaius Jenkins.

A New York native. Occupation - Tailor. Moved to Kansas in the fall of 1854 (Connelly

1925). Brought to Camp Sackett after May

21 (Brown 1880).

John Brown, Jr.

An Ohio native. Son of John Brown. He and Henry H. Williams

were brought to Camp Sackett in mid-June.

Henry H. Williams.

A New York native.

Came to Kansas in Spring 1855. 3rd

settler on Pottawatomie Creek in Anderson County. A commander in the Pottawatomie Guards, a

group which worked with John Brown to secure the Pottawatomie Creek area in

Anderson County. Williams was a delegate

to Big Springs Convention in 1855. He

was also a member of House of Representatives under Topeka Constitution. (KSHS 2018).

Charles Robinson.

A Massachussetts native.

He arrived in Kansas in 1854 with the New England Emigrant Aid Company’s

first colony in Kansas Territory.

Elected governor under Topeka Constitution. Arrived at Camp Sackett after May 24th

(Brown 1880).

George W. Dietzler.

A Pennsylvania native. Dietzler moved to Lawrence in Spring

1855. He was involved in the Wakarusa War in November 1855, as an aide as well

as commanding officer.

Capt. John W. Martin who was given care of the prisoners for a time, was a member of the Kickapoo Rangers a pro-slavery contingent, but was partial to Charles Robinson, and provided the prisoners limited freedoms. The prisoners were allowed visitors, primarily their wives, but also extended to certain members of the free state alliance. Sara Robinson is known to have visited the camp (Robinson 1856), and Lois Gleason Brown wife of George W. Brown and her sister Annis Gleason also visited (Freeport Daily Journal 1856).

The prisoners were held at Camp Sackett with a promise of a hearing in early June, but their release was not to happen until early fall. By the fall, when conditions improved the prisoners posted their own bond and were released.

Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke reported that by mid-June the “Kansas dispute had changed in nature as the emotional situation had attracted lawless men who regularly resorted to banditry and murder” (Ewy 1966: 392). During this time troops stationed at Sackett included both the 1st Cavalry, 2nd Dragoons, and 6th Infantry (Ewy 1966).

There was an increase in U. S. military troops in direct relationship to the hostilities in the area (Table 1). In mid-September after the battle of Hickory Point, the troops brought Free-State forces, about 100 prisoners, who had been under command of J. A. Harvey in that skirmish to Lecompton (Ewy 1966)*. The increase in hostilities in August and September (at Osawatomie, Fort Titus, Hickory Point, etc…) increased the number of troops at Sackett’s location with 500 men in August, and 700 men in September (Coakley 2011). Another influx of prisoners arrived in October when Lt. Col. Philip St. G. Cooke and U. S. Deputy Marshal William J. Preston captured 240 free-staters which included Shalor Eldridge and Samuel Pomeroy (Coakley 2011).

As conditions settled in the territory troops were dispersed to other duties. In early November the troops at Lecompton had been reduced to two companies of the 1st Cavalry and one company of the 6th Infantry and by the end of November only the one company of 6th Infantry remained (Coakley 2011:170).

1856 was the most turbulent year in the era of Bleeding Kansas, which prompted the need for this military installation. Wilson Shannon, who was Territorial Governor during this time, illustrated this with my favorite Bleeding Kansas quote, “Governing Kansas during 1856 was like trying to govern the Devil in Hell.”

References Cited

Brown, G. W.

1880 Reminiscences of Old John Brown: Thrilling Incidences of Border Life in

Kansas. Abraham E. Smith, Rockford, IL.

Coakley, Robert W.

2011 The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1789-1878.

Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C.

Connelly, William E.

n.d. Douglas County, Kansas Territory in the Era of Bleeding Kansas. Map

on file at the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, KS.

1925 “The Lane-Jenkins Claim

Contest.” Collections of the Kansas State

Historical Society, 1923-25, Vol. 16, pp.25-27.

Ewy, Marvin

1966 “The United States Army in

the Kansas Border Troubles”. In Kansas

Historical Quarterly. Vol. 32, pp.

385-400.

Freeport Daily Journal

1856 “Kansas Correspondence” Freeport Daily Journal (newspaper),

Freeport, Illinois. July 7, 1856.

Kansas Historical Society

2018 “Henry Hudson

Williams”. Biography found on-line at: http://www.kansasmemory.org/item/439582

Lowe, Percival G.

1906 Five Years a Dragoon. The Franklin Hudson Publishing Co., Kansas

City, MO.

Mullis, Tony R.

2004 Peacekeeping on the Plains: Army Operations in Bleeding Kansas. University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO.

Robinson Charles

1892 The Kansas Conflict. Harper

& Brothers, Franklin Square, New York, NY.

Stuck, J. Cooper

1857 Map of Douglas County,

Kansas Territory.

*this formerly read that J. A. Harvey brought the men to Lecompton.

*this formerly read that J. A. Harvey brought the men to Lecompton.