Pension records are precious documents that offer up information that might not normally be obtained from the usual sources. Among all the facts offered, is also the opportunity to hear the "voice" of those giving statements in regards to the veteran in question. This became strikingly obvious when I was recently reading through the pension application for former veteran Frank Austin by his widow Lizzie. Frank had served in Company F of the 83rd United States Colored Troops (2nd Kansas Colored), and passed away in 1902. In her statements as a claimant for Frank's pension, Lizzie gave more than just the facts for the pension examiner, she gives us a glimpse into her personality. In relaying her connection personal history to the examiner, she relates time to the "Holidays".

While this is important in ascertaining that important dates for a

family tree, the repetition of the statement also shows the importance

of the season to Lizzie.

When looking at your pensions, don't forget to read between the lines, your people might be saying more than you think they are!

We wish you your own historic holiday season! ;)

Tuesday, December 24, 2019

Wednesday, October 2, 2019

Taking a Look at a Page

Recently I was conducting some research for a book I’m

writing and was delving into the realm of the legislative panels at the Kansas

Historical Society in order to find portraits of some key individuals for that

project. Early panels are rather simple, became more complex through the years as

the state grew and more features started appearing within them – pictures of

anyone associated with legislative activities (doorkeepers, sergeant at arms,

clerks, etc…). One feature that caught my eye was pictures of children like

this one of the 1875 House of Representatives:

Who are they? Was the answer as simple as the youth being

legislative pages? If so, the African American boy may be easy to identify

because he would be a rarity for this time societal views on people of color. I love tackling bunny trails like

this because they present a challenge – it’s like a personal check on my

research skills. Actually, I may need a twelve-step program for it, but we’ll

go with the former because using it to continue my education sounds better

right? ;) The short answer to my question is – yes! They are pages.

Becoming a page at this time was highly competitive,

applicants would at times number more than a couple of dozen, with just a

handful being selected for the honor. “There is a young army of little boys

and girls seeking positions of page in both houses of the legislature, and some

of them display remarkably fine judgment in electioneering and presenting their

respective claims for the positions they are seeking.” (Holton Express

1875:2).

Narrowing down the number of applicants for the final

selection of Senate pages in 1875 was so intense that the Senate took a

25-minute recess and then went directly into caucus to decide upon two page

positions (Daily Commonwealth 1875:1). For the House of Representatives in 1875

(above picture), selection was finally made for Josie Bell, Charles Jones, Emma

Duncan, Minnie A. Scrafford, Jennie Maxwell, and Thomas Taylor (Wyandotte Gazette 1875:2).

The page’s residence like today was not limited to just the

surrounding area, which begs the question of how the duties were worked around

their school terms. Jennie Maxwell, however, of the House pages was from

Topeka. A bright and responsible student, this was Jennie’s second time as a

legislative page; she first served in 1871 at the age of 12. At the end of the

1875 session, she was named specifically by the legislature for her and “the

other pages for the unvarying courtesy, thoughtful attention and marked

promptitude and ability with which each and all have discharged their several

duties” (Atchison Weekly Patriot 1875:2). Duties for the pages were much like they are today, carrying messages,

bringing water to the representatives, etc… (Winfield Courier 1876:2).

Despite her age at the time of her first term of service in

1871, Jennie was accepted into a group of women who met at the Tefft House

(owned by Charles Jennison of Kansas Civil War notoriety) that were active in

various positions in the legislature, such as clerks (Kansas State Record 1871:4). The suffrage movement had

started gaining momentum in the early 1870s and legislative positions were

freeing for women and allowed them a chance to take part in the political

process even before they were allowed to vote.

Allowances as clerks and pages were still disputed among

some legislators that held anti-suffrage views. Such is the case in 1876 when

Rosa Blanton was chosen as a page to the House of Representatives (Rosa was the

niece of Napoleon Blanton who was well known in early Kansas for his crossing

of the Wakarusa River in Douglas County):

“There were twenty-seven candidates for pages, and the

discussion on the claims of each was earnest, spirited and prolonged. Mr.

Eskridge made an eloquent speech in favor of a young man named Blanton, stating

that he was prompted in his efforts in favor of his candidate at the request of

a brother member, Mr. Wood, who was now absent. After Mr. Eskridge had

concluded his thrilling effort in favor of his candidate, the young man, and

had taken his seat, he again rose and stated that he had been mistaken in the

sex of his candidate – that it was a young lady – Rosa Blanton, whom he wished

to have elected. This statement was received with shouts of laughter, the

well-known opposition of Mr. Eskridge to female suffrage doubtless contributing

to the amusement. Mr. Eskridge gracefully relieved himself from his embarrassment

by explaining that it was the principle he was contending for, not personal

preferences" (Kansas Daily Tribune 1876:5).

Women were not the only ones that found empowerment though

legislative positions. In 1875, John Carter who was a man of color from Topeka,

was elected to the position of assistant doorkeeper (Winfield Courier 1876:2).

Mr. Carter was the only individual in the legislature in that year, aside from

the aforementioned young page, to be of African descent. The doorkeeper

position was the only position allowed to speak during legislative proceedings,

announcing the various members. An 1885 panel showed an African American man,

Sam Lee of Lawrence, that held the assistant doorkeeper position. He was paid $3 a month

for his service (CITE).

I finally had to tear myself away from all the bunny trails

that arose from looking at these panels. It is something that would be fun to

return to again. Many of the Kansas panels can be found on www.kansasmemory.org, search term

“legislative panel.”

References Cited:

Atchison

Weekly Patriot

1875 Atchison Weekly Patriot (newspaper),

Atchison, KS. March 13, 1875, page 2.

Daily

Commonwealth

1875

"Kansas Legislature". Daily Commonwealth (newspaper), Topeka,

KS. January 13, 1875, page 1.

Holton Express

1875 Holton

Express (newspaper), Holton, KS. January 15, 1875, page 2.

Kansas Daily Tribune

1875 “House”,

Kansas Daily Tribune (newspaper), Lawrence, KS, January 15, 1876, page

5.

Kansas State Record

1875 “A

Levee”, Kansas State Record (newspaper), Topeka, KS. January 10, 1871,

page 4.

Winfield Courier

1876 “Conclusions

Concerning Capital City Carpet Baggers”, Winfield Courier (newspaper),

Winfield, KS. February 17, 1876, page 2.

Wyandotte Gazette

1875 “Legislature

Organized”. Wyandotte Gazette (newspaper), Wyandotte, KS. January 15,

1875, page 2.

Friday, July 12, 2019

Ewing L. Moxley

The background research our company performs prior to

archaeological investigations causes me to dig in for the earliest historical

accounts of an area. I love digging in deep, finding information to make our

reports more than just names and dates. Trying along the way to ferret out the

whys behind the locations we investigate. One of my hobbies (I have many that

I’ve picked up in my background research) is documenting trading posts and

traders. The fascinating stories that follow these guys captivate me. My newest

bunny trail caused me to follow Ewing L. Moxley, a trader among the tribes in

Sedgwick County, Kansas.

Moxley grabbed my attention because in my quest to find out his

importance to the area, I found actual descriptions of his physical appearance

as well as his character. He is described as having a fair complexion, with

“light hair and whiskers” (Oskaloosa Independent 1863: 3) and as being “a

thorough frontiersman, born in the wilds, an unerring marksman, fearless,

honest and simple and tender as a child” (Mooney 1916:105).

Moxley and his trading partner Edward H. Mosely were among

the first Euro-Americans in Sedgwick County, Kansas. Moxley’s background is rather

hazy. He is potentially born prior to 1837, the son of Judge Solomon R. Moxley

of Lincoln County, Missouri, but that remains to be proven (Goodspeed Pub. Co.

1888: 583). His partner Mosely was an Indiana native (Medicine Lodge Cresset

1886). The two were noted as first

meeting in Coffey County, Kansas around present day LeRoy (Mead 1986: 139; Medicine

Lodge Cresset 1886). Apparently, Mosely and Moxley attempted farming, but on

account of the drought found a more profitable business in trading. It is

highly probable that their early introduction to trading could have been by utilizing

trade along an Osage trail at the nearby Burlington Crossing (Burns 2004:75)

In 1857, the two were among the first settlers in Sedgwick County

and established a mercantile or trading post on the Little Arkansas River where

an Osage trail crossed. The pair capitalized on the buffalo hunting in the area

and would sell the surplus of their hunts as well as other trade goods to the

inhabitants of the surrounding area (Medicine Lodge Cresset 1886). This was the

first “ranch” in the county along with one established by Bob Duracken a few

miles away, but it consisted of little more than a cabin on a claim but was

profitable for the pair.

By 1858, Moxley was in Butler County in the Chelsea area.

Chelsea, now defunct, was an up and coming town in this period and was at this

early date the county seat of Butler County (Mooney 1916: 54). Butler was among

the first 36 counties established with the organization of Kansas Territory.

Even with his travels, Moxley’s home base was in Jefferson

County, which further intrigued me because that is the home base of Buried Past!

In 1857, with the sale of the Delaware lands in that county, Moxley purchased

the northwest 1/4 of Section 19, Township 8 South, Range 20 East for farming

purposes. He is noted as working with two other settlers of the area, George W.

Crump and Joseph Hicks to establish a territorial road from Crump’s land in

Section 9 of the same Township/Range to Osawkee (now near modern-day Ozawkie) (State

of Kansas 1861:317).

When the war erupted Moxley ran what famed buffalo hunter

James R. Mead called a “side show” to the Union army, picking Confederates off

their horses with his Sharp’s rifle or Navy revolver and taking their horses

for his pay (Mead 1986: 140; Moxley 1865). Moxley met his end while attempting to

swim some of his contraband stock across the Kansas River at nearby Lawrence. His

short but varied career gathered a sizeable estate valued at $1200.99 and no

one around to claim it (Oskaloosa Independent 1863; Moxley 1865). He had

limited contact with his family at the end of his life, and his final resting

place is unknown (Moxley 1865).

~wmb

Burns, Louis F.

2004 History of

the Osage People. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL.

Goodspeed Publishing Company

1888 History of

Lincoln County, Missouri, from the Earliest time to the Present. The

Goodspeed Pub. Co. Chicago, IL.

Mead, James R.

1986 Hunting and

Trading on the Great Plains, 1859-1875. Rowfant Press, Wichita, KS.

Medicine Lodge Cresset

1886 “Our Early

Settlers” Medicine Lodge Cresset (newspaper), Medicine Lodge, KS. May 27, 1886,

p. 1.

Mooney, Vol. P.

1916 History of

Butler Co., Kansas. Standard Publishing Co., Lawrence, KS.

Moxley, Ewing L.

1865 Probate Case Files (Estates), ca. 1858 - 1917; Indexes, ca. 1860-1960; Author: Kansas. Probate Court (Jefferson County); Probate Place: Jefferson, Kansas, No. 416. Accessed on-line: Ancestry.com.

Oskaloosa Independent

1863 “Notice to

Unknown Heirs”, Oskaloosa Independent (newspaper), Oskaloosa, KS. August 8, 1863, p.3.

State of Kansas

1861 House

Journal (Extra Session) of the Legislative Assembly of Kansas Territory for the

Year 1857. Sam. A. Medary, Printer, Lawrence, KS.

Tuesday, May 7, 2019

Bleeding Kansas: Camp Sackett

|

| Image of Camp Sackett taken from a daguerrotype and published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, October 4, 1856. |

As conditions deteriorated within the newly established

Kansas Territory, the need for a neutral military force became apparent to keep

the peace (Table 1). The first Territorial

legislature, also called the “Bogus Legislature” had established a pro-slavery

government within Kansas Territory and was upheld by President Pierce. In

February of 1856, Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cook received instructions from

the Secretary of War that troops were to be used within the Territory. On March 26, Colonel Edwin V. Sumner enlisted

the government troops in the growing conflict between free-state and

pro-slavery forces (Robinson 1892).

|

| Table 1: Timeline for troops at Camp Sackett within Kansas Territory events in 1856. |

Troops in Kansas Territory were stationed near military roads at Westport,

Franklin, Baldwin City, Lecompton (Lowe 1906:226) and other strategic

communities and planned as headquarters from which troops could move quickly

when necessary, with food and supplies arriving every ten days (Lowe 1906). In

the spring of 1856, the territorial capital was moved to Lecompton from Shawnee

Mission. This area was then chosen for a primary camp for the government troops

with easy access to the capital. Access to the camp would primarily have been

the Lecompton to Big Springs Road or the California Road (Stuck 1857, Connelly

n.d.).

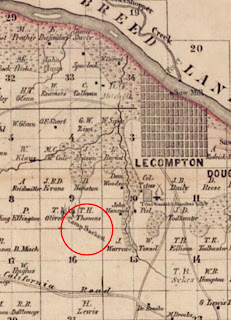

|

| 1857 Douglas County map by J. Cooper Stuck which shows the location of Camp Sackett in relation to Lecompton and roadways. |

First deployment to the camp was a group of troops under Lt.

James McIntosh around April 23rd, followed by two squadrons under

Col. Sumner (Ewy 1966: 389). The camp

was named for Lt. Col. Delos B. Sackett, the commanding officer early in its

establishment. This camp seems to be

commonly called “Camp Sackett” primarily by those stationed at the camp. Within

the newspaper reports, the camp was known as “the treason camp, near

Lecompton”, “the camp near Lecompton”, or “the U.S. military camp near

Lecompton”. Charles Robinson in his book, The

Kansas Conflict calls it the “Treason Camp” (Robinson 1892). Any designations, however, referring just to

the “camp near Lecompton” should be analyzed and not be confused with the

Titus’ pro-slavery camp near Lecompton.

Titus’ camp is primarily designated as “the pro-slavery camp” but on

occasion is also only called the “camp near Lecompton”.

United States military troops again deployed to the Lecompton

area around May 23rd when Governor Wilson Shannon requested one

company of the 1st Cavalry was to be posted near Lecompton and

another company near Topeka (Mullis 2004). Later, in early June, Lt. Col. Philip

St. George Cooke would arrive from Fort Riley with a compliment of 2nd

Dragoons consisting of 134 men, 124 horses, and one artillery piece (Coakley

2011: 157).

Beginning on and around May 20 (Brown 1880), political

prisoners charged with high treason were delivered to the military camp:

Charles Robinson, George W. Brown, George W. Smith, George W. Deitzler, John

Brown, Jr., and Henry H. Williams. The

charge of treason was imposed on these individuals for supporting a free-state

government and enforced because the pro-slavery government established in 1855 along

with the Topeka Constitution had been federally recognized. Sara Robinson, in

her book Kansas: Interior and Exterior Life gives Camp Sackett the nickname

“Uncle Sam’s Bastille on the Prairie” because of the imprisonment of her

husband and the other men accused of treason.

|

| Left to Right: George W. Brown, John Brown, Jr., George W. Smith, Charles Robinson, Gaius Jenkins, Henry H. Williams, George W. Dietzler. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, October 4, 1856. |

Five political prisoners held on “Traitor Avenue” at Camp

Sackett are as follows:

George W. Smith.

A Pennsylvania native.

Occupation - Judge. Elected by the free-state legislature to serve as

the second territorial governor.

George W. Brown.

A New York native. Occupation - Editor of the Kansas Herald

of Freedom published in Lawrence. He and

Gaius Jenkins were arrested at Westport, MO.

Brown reached the Lecompton camp on May 20 (Brown 1880).

Gaius Jenkins.

A New York native. Occupation - Tailor. Moved to Kansas in the fall of 1854 (Connelly

1925). Brought to Camp Sackett after May

21 (Brown 1880).

John Brown, Jr.

An Ohio native. Son of John Brown. He and Henry H. Williams

were brought to Camp Sackett in mid-June.

Henry H. Williams.

A New York native.

Came to Kansas in Spring 1855. 3rd

settler on Pottawatomie Creek in Anderson County. A commander in the Pottawatomie Guards, a

group which worked with John Brown to secure the Pottawatomie Creek area in

Anderson County. Williams was a delegate

to Big Springs Convention in 1855. He

was also a member of House of Representatives under Topeka Constitution. (KSHS 2018).

Charles Robinson.

A Massachussetts native.

He arrived in Kansas in 1854 with the New England Emigrant Aid Company’s

first colony in Kansas Territory.

Elected governor under Topeka Constitution. Arrived at Camp Sackett after May 24th

(Brown 1880).

George W. Dietzler.

A Pennsylvania native. Dietzler moved to Lawrence in Spring

1855. He was involved in the Wakarusa War in November 1855, as an aide as well

as commanding officer.

Capt. John W. Martin who was given care of the prisoners for a time, was a member of the Kickapoo Rangers a pro-slavery contingent, but was partial to Charles Robinson, and provided the prisoners limited freedoms. The prisoners were allowed visitors, primarily their wives, but also extended to certain members of the free state alliance. Sara Robinson is known to have visited the camp (Robinson 1856), and Lois Gleason Brown wife of George W. Brown and her sister Annis Gleason also visited (Freeport Daily Journal 1856).

The prisoners were held at Camp Sackett with a promise of a hearing in early June, but their release was not to happen until early fall. By the fall, when conditions improved the prisoners posted their own bond and were released.

Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke reported that by mid-June the “Kansas dispute had changed in nature as the emotional situation had attracted lawless men who regularly resorted to banditry and murder” (Ewy 1966: 392). During this time troops stationed at Sackett included both the 1st Cavalry, 2nd Dragoons, and 6th Infantry (Ewy 1966).

There was an increase in U. S. military troops in direct relationship to the hostilities in the area (Table 1). In mid-September after the battle of Hickory Point, the troops brought Free-State forces, about 100 prisoners, who had been under command of J. A. Harvey in that skirmish to Lecompton (Ewy 1966)*. The increase in hostilities in August and September (at Osawatomie, Fort Titus, Hickory Point, etc…) increased the number of troops at Sackett’s location with 500 men in August, and 700 men in September (Coakley 2011). Another influx of prisoners arrived in October when Lt. Col. Philip St. G. Cooke and U. S. Deputy Marshal William J. Preston captured 240 free-staters which included Shalor Eldridge and Samuel Pomeroy (Coakley 2011).

As conditions settled in the territory troops were dispersed to other duties. In early November the troops at Lecompton had been reduced to two companies of the 1st Cavalry and one company of the 6th Infantry and by the end of November only the one company of 6th Infantry remained (Coakley 2011:170).

1856 was the most turbulent year in the era of Bleeding Kansas, which prompted the need for this military installation. Wilson Shannon, who was Territorial Governor during this time, illustrated this with my favorite Bleeding Kansas quote, “Governing Kansas during 1856 was like trying to govern the Devil in Hell.”

References Cited

Brown, G. W.

1880 Reminiscences of Old John Brown: Thrilling Incidences of Border Life in

Kansas. Abraham E. Smith, Rockford, IL.

Coakley, Robert W.

2011 The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1789-1878.

Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C.

Connelly, William E.

n.d. Douglas County, Kansas Territory in the Era of Bleeding Kansas. Map

on file at the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, KS.

1925 “The Lane-Jenkins Claim

Contest.” Collections of the Kansas State

Historical Society, 1923-25, Vol. 16, pp.25-27.

Ewy, Marvin

1966 “The United States Army in

the Kansas Border Troubles”. In Kansas

Historical Quarterly. Vol. 32, pp.

385-400.

Freeport Daily Journal

1856 “Kansas Correspondence” Freeport Daily Journal (newspaper),

Freeport, Illinois. July 7, 1856.

Kansas Historical Society

2018 “Henry Hudson

Williams”. Biography found on-line at: http://www.kansasmemory.org/item/439582

Lowe, Percival G.

1906 Five Years a Dragoon. The Franklin Hudson Publishing Co., Kansas

City, MO.

Mullis, Tony R.

2004 Peacekeeping on the Plains: Army Operations in Bleeding Kansas. University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO.

Robinson Charles

1892 The Kansas Conflict. Harper

& Brothers, Franklin Square, New York, NY.

Stuck, J. Cooper

1857 Map of Douglas County,

Kansas Territory.

*this formerly read that J. A. Harvey brought the men to Lecompton.

*this formerly read that J. A. Harvey brought the men to Lecompton.

Wednesday, April 3, 2019

Buried Bunny Trails

This blog has been a long time coming. CRM archaeology doesn't allow much time for blogging, so we'll see how this goes....

Why this blog? Well, we find a ton of interesting tidbits in our many projects

across the Plains, and one of the side goals we’ve always had for our business

is to be able to educate the public on history that is unseen. That goal is actually two-fold:

1) We want to share about what we do and why we do it (because if you don’t know why cultural resources are important, why would you want to protect them?)

1) We want to share about what we do and why we do it (because if you don’t know why cultural resources are important, why would you want to protect them?)

~and~

2) We don’t like to keep the past buried, we want people to

get as excited about what we uncover as we are!

As the historian of this outfit, I am always finding

fascinating stories that I want to flesh out more than time allows when we’re

on our projects. My bunny trails. My research buddies know I’m a sucker for

them ;) Some bunny trails just become interesting bits of trivia that I can spout off in

general conversation and some I make my “pet projects”. I have a few that I’ve been gathering

information on for months upon months but don’t yet have an outlet for them. Other

things I pick up are are tricks of the trade as a researcher. I would love to

share these with fellow archival diggers of the past – something to aid in getting around some

brick walls. And other things will be general historical randomness ;) If you follow our Facebook page you'll know that we're kind of random - either by jumping from project to project, or even just something cool historical that catches our eye! So to you, dear reader, I’m extending an invitation to follow me

down some of my random bunny trails.

Maybe by writing my bunny trails down in this blog, it

will help me not to bury the knowledge gained once again, but help someone else

discover some cool buried past!

Thanks for joining in!

~Wendi

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)